The 6888th Central Directory Postal Battalion in the ETO

Alexander Braun • January 18, 2025

No Mail, No Morale -

The "Six Triple Eight" in the ETO

The Netflix movie

Two weeks ago, I watched the Netflix movie "The Six Triple Eight", which was released on December 20, 2024, and was directed by Tyler Perry. The movie is about a Women's Army Corps (WAC) battalion of African-American women who serve in the European Theater of War during the final stages of World War II.

The news of the film's release piqued my interest because three women from this battalion are buried in the Normandy American Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer. When I visit the cemetery with its 9,388 headstones on a tour with clients, I always point out the three headstones of Private First Class Mary J. Barlow (age 21) and Sergeant Dolores Mercedes Brown (age 23), both from Connecticut, and Private First Class Mary Hortensa Bankston (age 24), from New York.

The tree women were involved in a tragic automobile accident on July 8, 1945, while riding in a jeep with some male soldiers. Both Marys were killed instantly; Dolores lingered for five days before succumbing to her injuries on July 13, 1945. The three women were buried first in the temporary U.S. cemetery at St. André and later moved to the Normandy American Cemetery.

History of the Central Directory Post Battalion

The 6888th Central Directory Postal Battalion, nicknamed the "Six Triple Eight 6888th," was the only all-black Women's Army Auxiliary Corps unit deployed to Europe during World War II. Led by Major Charity Adams, the Six Triple Eight deployed to Birmingham on February 12, 1945, where they undertook the mammoth task of sorting 17.5 million letters and parcels for delivery to approximately 3 million U.S. personnel in the European Theater of War (ETO).

Fighting for the Right to Serve

In the summer of 1944, Major Charity Adams was charged with preparing a Women's Army Corps (WAC) battalion of black Americans for overseas deployment. Although their mission had not yet been determined, the women threw themselves into a training program that included obstacle courses, gas mask drills, and lectures on aircraft identification. As the women prepared for their future mission, African American political and civil rights leaders lobbied the government for the opportunity for Black American women to serve overseas. In December 1944, the War Department relented, and the decision was made to form a Postal Directory Battalion to serve in the European Theater. A major factor in the decision was the urgent need for more postal workers to handle the huge backlog of mail that had accumulated in Europe since the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944. The 6888th Central Postal Directory was created under the leadership of Major Charity Adams.

The personnel of the Six Triple Eight (the battalion was 855 strong, 824 enlisted women and 31 officers) were drawn from the ranks of the Women's Army Corps, with a requirement of willingness to serve overseas. There was no shortage of volunteers. Many of the battalion's sergeants were trained medical technicians who had worked in hospitals before being selected for the Six Triple Eight. Despite the mismatch between their specialties and their eventual assignments, many servicewomen jumped at the chance to serve in a combat zone. One of the many obstacles African-American WACs faced was a reluctance within the U.S. Army to assign women to specialized roles. Instead, they often served as generalists, performing menial tasks such as cleaning and laundry, even though most WACs were highly educated. As part of their training, the WACs of the Six Triple Eight Central Postal Battalion received instruction on the U.S. postal system from postal clerks.

Arrival in Great Britain

The Six Triple Eight boarded the liner Île de France on February 3, 1945 and encountered several German U-boats on the transatlantic crossing. It wasn't until the ship was halfway across the Atlantic that the women were told they were being sent to Britain. On February 11, the Île de France docked in Glasgow and the battalion was boarded onto a train for Birmingham in the English Midlands, arriving late on the evening of February 12. As the women traveled to their billets, they were amazed at the bomb damage that had been done to the city.

The reception they received from the local population was warm and curious. While some locals held racist views, others were quick to extend invitations to the new arrivals. African Americans had been sent to Britain since 1942, but were concentrated in the southwest and east of England. During their time in Birmingham, the Six Triple Eight were housed at King's Edward School in Edgbaston, a requisitioned boys' boarding school that, according to new arrival Evelyn Johnson, was ill-equipped to accommodate women.

No mail, low morale

The Six Triple Eight would work in six drafty warehouses piled high with more than 17 million pieces of unsorted mail and overrun with rats that feasted on the rotting parcels of homemade cakes and fried chicken sent to soldiers by well-meaning loved ones in the United States. The delay in processing the mail was caused in part by the transient nature of the invading forces as personnel advanced across Europe. Another stumbling block was the incomplete or outdated addresses on the envelopes, which were further complicated by the sheer number of personnel with the same name (for example, there were approximately 7,500 Robert Smiths serving in the ETO). The Six Triple Eights were given six months to deal with this enormous backlog.

The War Department had reason for urgency. The mail had long been seen as an important morale-booster. Writing in 1942, the United States Postmaster General argued that "frequent and rapid communication with parents, comrades, and other loved ones strengthens fortitude, revives patriotism, makes loneliness bearable, and inspires to greater devotion the men and women who carry on our fight far from home and friends. In the words of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion's motto, "No mail, low morale".

Under the steady leadership of Major Charity Adams, the battalion was organized into three shifts and worked around the clock to eliminate the backlog of mail. The battalion developed and implemented a system to reunite orphaned mail with its intended recipient. A locator clerk updated boxes of maps that tracked the locations of U.S. units overseas. Meanwhile, mail clerks were given an alphabetical list of names and associated units to use in processing incoming mail. At its peak, the Six Triple Eight numbered 855 women, divided into a headquarters company and four postal companies. The three shifts each processed about 65,000 pieces per shift, or about 195,000 pieces per day. The battalion stayed in Birmingham for three months, or 90 days. During that time, the Six Triple Eights sorted and redistributed approximately 17.5 million pieces of mail.

Off Duty

Not every member of the battalion was a postal worker. The Six Triple Eight also included administrative personnel, cooks, and Special Service personnel who ran the unit's recreation program.This recreational program was the unit's variety show, "Wacacts".

The show was performed for the Lord Mayor of Birmingham and later toured British hospitals and G.I. bases as part of an Anglo-American troupe.

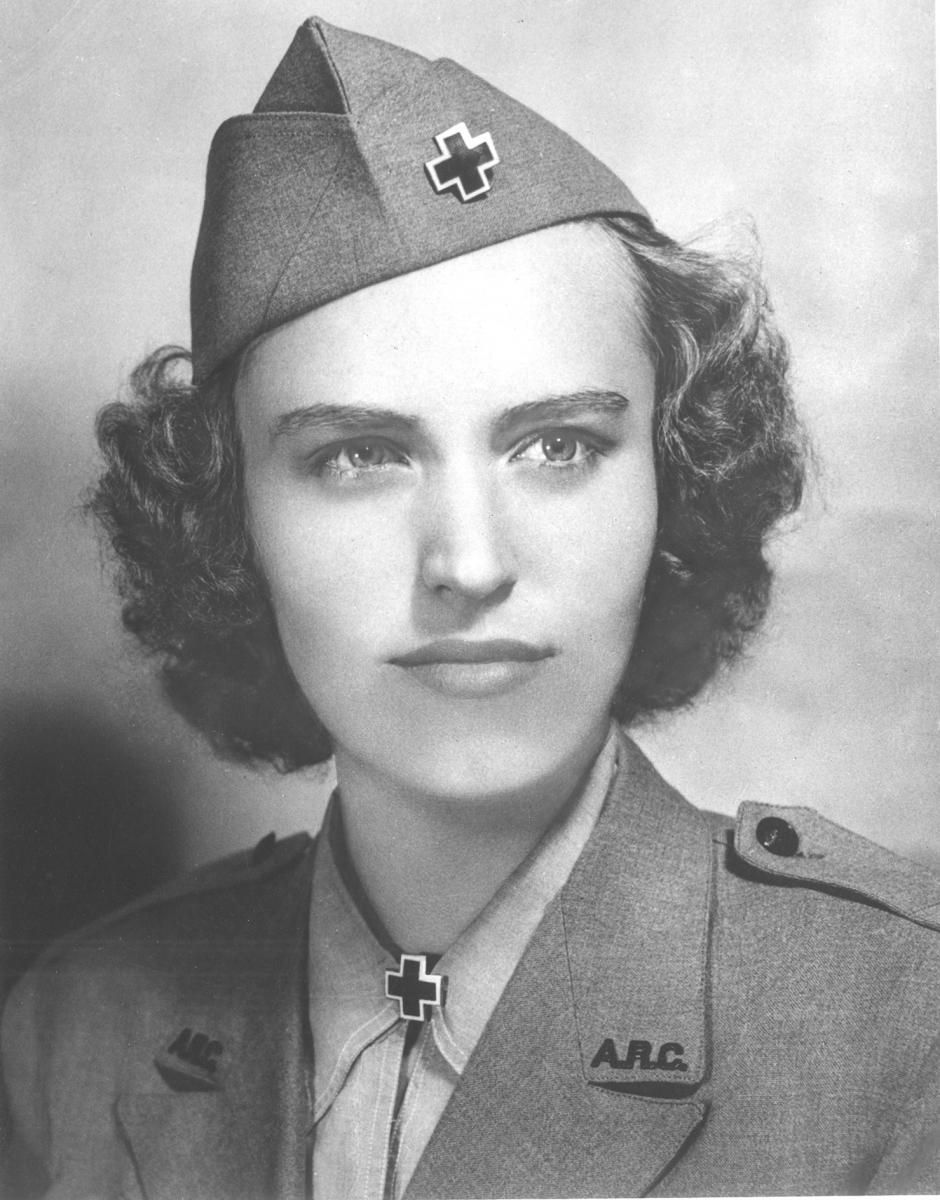

During their allotted leave, the WACs visited towns and cities throughout Britain, with London being the most popular destination. On one occasion, the entire unit was sent to London to parade before Mary, the Queen Mother. Despite the warm welcome from the majority of the British people, the women of the Six Triple Eight found hostility and discrimination within the U.S. military. A policy of segregation meant that Black Americans were often prevented from using facilities reserved for white servicemen. This extended to American Red Cross clubs, which operated white and black service clubs, although they publicly denied that their services were segregated. In London, the American Red Cross offered to provide Six Triple Eight personnel with their own hotel. Major Charity Adams knew it was so her troops wouldn't have to use the accommodations set up for white servicewomen.

A new challenge in France

After completing their work in Birmingham in May 1945, the battalion received orders to move to Rouen, France, and do the same work there. Once again, the Six Triple Eights were able to complete the backlog in less time than they were allotted.

Tragedy struck the battalion on July 8, 1945, when three WACs were killed in a vehicle accident while on duty. Private Mary J. Barlow and Sergeant Dolores Mercedes Brown, both of Connecticut, and Private First Class Mary Hortensa Bankston of New York were interred at the American Cemetery on Omaha Beach, Normandy. Shockingly, the U.S. Army did not provide funds for their burial, so the members of the 6888th took up a collection, and several members of the unit were familiar with mortuary duties.

From Rouen, the battalion moved to Paris, where personnel were slowly rotated home from the summer of 1945 until February 1946, when the unit returned to the United States.

At the end of their tours, some women remained in the military, but most returned to civilian life, often sharing little of their wartime experiences.

Recognition long overdue

In 2022, the battalion was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian honor bestowed by the United States Congress. On one side of the medal is a portrait of Adams, and on the other is a large stack of letters and parcels with the inscription "Clearing the Backlog". In 2023, a U.S. Army base named for Confederate General Robert E. Lee was renamed Fort Gregg-Adams in honor of the 6888's Adams and Arthur Gregg, another pioneering African American in the Army.

Paying your respects

If you visit the Normandy American Cemetery, either on your own or with a tour guide, please be sure to pay your respects to Sergeant Dolores Mercedes Brown (Plot F, Row 13, Grave 19), Private First Class Mary Hortensa Bankston (Plot D, Row 20, Grave 46), and Private First Class Mary Jewel Barlow (Plot A, Row 19, Grave 39).